Recently, I came across an article in World Archaeology, Volume 47, Issue 3, 2015 (see here or here). The article bears the title ´Was it for walrus? Viking Age settlement and medieval walrus ivory trade in Iceland and Greenland´, and is for most parts quite interesting. However, some of the contents regarding Iceland seemed to me to indicate that the Icelandic authors were totally unaware that similar research was being undertaken in Iceland.

However, after a quick browse through the article presenting an interesting study on how to work out the provenance of walrus tusks from the the Viking age and Medieval period, I found it quite worrying that the reader is not receiving a correct image of the status on walrus-research in Iceland.

To begin with the miniscule, I found it quite amusing to read that Novgorod has been moved up to the arctic near the White Sea. On page 454, where results presented in Table one are plotted into two diagrams (Fig. 2), the legend for figure 2 informs about the origin of the samples (with a closer definition in parentheses). We read that one of the samples originates from the excavations at Novgorod, and is provided by professor emerita Else Roesdahl of Aarhus University. In parentheses it also claimed that Novgorod is: "(Novgorod, White Sea, Russia)". Novgorod, which is 180 km south-east of present day St. Petersburg has of course never been anywhere near the White Sea. However, much later in the article things finally get clarified, also in a parenthesis. This explanation is given: "a medieval fragment from Novgorod (possibly representing an animal from the White Sea)". Actually there is therefore no certainty for the origin of the walrus tusk in Novgorod. There is only a tusk, lent by a Danish professor, and an assumption made by 13 authors of an article.

The claim that the walrus tusk sample from Novgorod, in the private collection of a Danish academic, is from the White Sea is but a minor detail compared to another critical item in an otherwise interesting study presented in the article.

The introduction on research in Iceland claims that an archaeologist colleague of mine, Bjarni F. Einarsson, has published results which support the following claim by the authors of the World Archaeology article: "Several authors (Vésteinsson et al. 2006; Keller 2010; Einarsson Bjarni 2011) have suggested that the first exploration and settlement of both Iceland (c. 850–75 ce) and Greenland (c. 980–90 ce) had an initial stimulus from exploiting the walrus, then native to both islands".

In fact Einarsson does not write that at all in his article of 2011 (see here). On the contrary, he wrote that the walrus stocks in Iceland in had declined and moved from Iceland long before the settlement in the 9th century, and not that it had been native to Iceland in the Settlement-period as argued in the 2015 study in World Archaeology here under scrutiny.

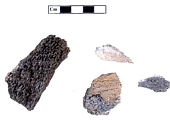

There is after all not much fact to support the claim that the first settlement of Iceland and Greenland was stimulated by demand for walrus-tusk. Einarsson also points out that there are only four radiocarbon dating results from Iceland of walrus tusks, and all of them show results which indicate that the animals in question lived 100-200 years BC, or even earlier. The tusks dated in Iceland were not from archaeological contexts. However, Einarsson is awaiting the results of AMS-radiocarbon analyses of a tusk found during an archaeological excavation of Viking-age farmhouses in the city-centre of Reykjavík (Ađalstrćti 2001). They might show a date corresponding with the date of the archaeological remains, or they could give dates indicating that the tusk was from walrus skeletons, which the first settlers in Iceland picked up on the shores.

Another aspect, which might indicate that the first Icelanders where not hunting walrus for the tusks, is the finding of a rib of a very young individual reported by Thomas Amorosi (1996) in his PhD thesis, which is mentioned in the World Archaeology article. The alleged walrus bones, collected in 1944, were not excavated archaeologically and if the bones are indeed walrus remains from a Viking-age strata, its presence does not indicate hunting for the tusk since the animal, if male, would not have had any because it was very young. The Reykjavik "Vikings" were most likely munching on walrus meat, making ropes out of the hides or using the fat as fuel for their lamps, or all of these things, but not specifically hunting for the tusk.

When participating in international teamwork, where the methodology of analysing the chemical composition of walrus tusk to decide on the origins of the walrus tusks seems very promising indeed, it is rather sloppy and inadequate to describe former research on Walrus in the North-Atlantic the way Vésteinsson, McGovern and Guđmundsson do, especially in a well esteemed journal like World Archaeology. Probably urged by the drive to be the first persons ever to have proposed an explanation for the importance of walrus hunting for the discovery of Greenland, it is rather sad, when such self-promotion bases upon misquotation, misinformation and at most wishful thinking.

Probably a non-Landnam situation

In future examinations on walrus hunting and trade in the North Atlantic, it has to be taken into account that some of the walruses, whose tusks are the focus of attention, can be ascribed to animals who lived and had breeding grounds in Iceland long before humans settled in Iceland. Thus dating of the material analysed is essential, if not more crucial than establishing whether the animal lived in Iceland or not. Dr. Bjarni F. Einarsson has very correctly pointed this out, while his colleagues in Iceland and their American associates omitted that important detail and instead referred to his work writing that it was in line with their own.

The Icelandic authors of the article in World Archaeology also left out information about an ongoing project in Iceland, which aims at dating archaeological as well as stray remains and finds of Walrus found in Iceland. That project has archaeologist Bjarni F. Einarsson as a partner (see here, here and here). The Icelandic project is doing what the study presented in World Archaeology should have done before the quest for a method to pinpoint the origin of the walrus was established. There is no sense in finding the origin of walrus tusks of the Viking era, if the tusks are more than 1000 years older. Why the the Icelandic authors of the study in World Archaeology didn´t try to establish contacts with the ongoing project in Iceland to achieve the best methodological results, is very difficult to understand.

An English translation and publication of Bjarni F. Einarsson´s article from 2011 would be important. Possibly his Icelandic colleagues would then understand it better, as they have obviously become so alienated from Icelandic that they cannot quote from it correctly. Collaboration is always important, but parts of the walrus-study presented in World Archaeology was not about collaboration at all.

Vilhjálmur Örn Vilhjálmsson, 6 February - 2016

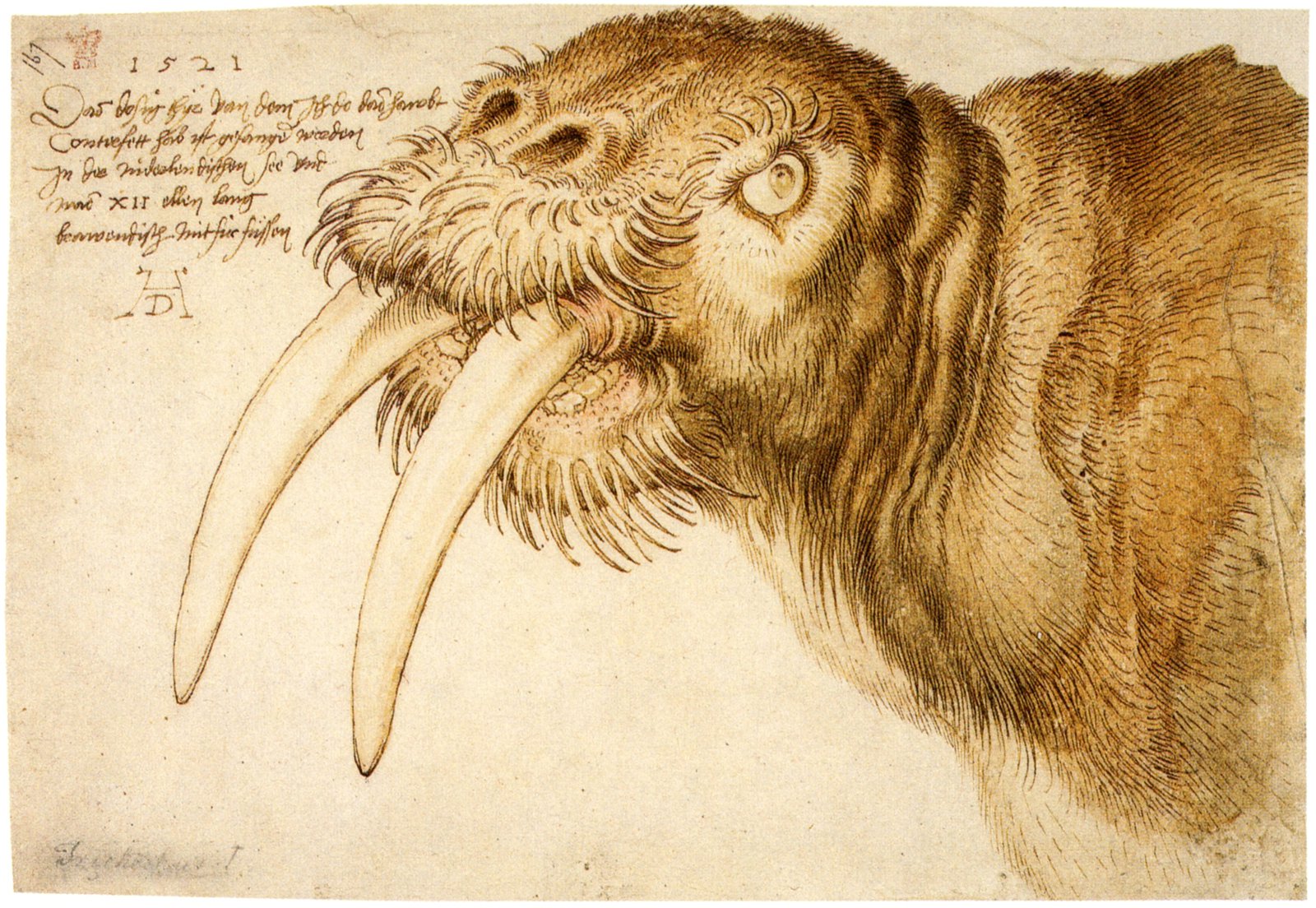

He´s obviously celebrating being the reason for the Landnam, but possibly a bit too early.

Meginflokkur: Forndýrafrćđi | Aukaflokkar: Landnám, Menning og listir | Breytt 9.12.2021 kl. 16:15 | Facebook

Athugasemdir

Ţakka Vilhjálmur góđa grein. Nágranni minn á tvćr ef ekki ţrjár Rostungstennur sem hann fann á jörđ sinni norđarlega sunnan megin á Snćfellsnesi. Hvort ţađ sé sérstakt eđa ekki ţađ gćti veriđ áhugavert ađ finna út síđan hvenćr ţađ er.

Valdimar Samúelsson, 7.2.2016 kl. 07:49

Bćta viđ athugasemd [Innskráning]

Ekki er lengur hćgt ađ skrifa athugasemdir viđ fćrsluna, ţar sem tímamörk á athugasemdir eru liđin.